This blog post is going to be somewhat longer and more technical than usual. It is intended as documentation for the use of IS staff, but may be more widely useful (at least in parts). To start with emails come in two parts – a header section, and one or more body parts.

You can do some analysis of the body of the email, but what can be done there is rather limited and has been covered before. However to go for a deep dive into the technicalities we need to have access to the full headers of the email.

Another thing to remember is that there is no guarantees on any of the signs in the headers (or the body) of faked/malicious emails; it’s a game of probabilities – if you get one or two indications that things are a bit “off” then it could well be legitimate; if you get many signs then it is most likely not legitimate.

The Raw View

This is a legitimate email … and the headers are rather scary :-

Delivered-To: someone@port.ac.uk

Received: by 2002:a4a:80c4:0:0:0:0:0 with SMTP id a4csp5624563oog;

Thu, 7 Jul 2022 07:01:05 -0700 (PDT)

X-Google-Smtp-Source: AGRyM1txkbSraTKe9LYdHuciBI/kNXNlcAgkNZT9pxAwqYxVJeD0ZhOER+04vWiJl4T99ZxoHX7b

X-Received: by 2002:a17:90b:1b41:b0:1ec:747c:5d1 with SMTP id nv1-20020a17090b1b4100b001ec747c05d1mr5435707pjb.213.1657202464930;

Thu, 07 Jul 2022 07:01:04 -0700 (PDT)

ARC-Seal: i=1; a=rsa-sha256; t=1657202464; cv=none;

d=google.com; s=arc-20160816;

b=tMx01iiG936FOOZW5sN4b6L7hQYIzEt6DinePrQYAeefM9UQEGLxQyKYSPZ5KSFfjx

fPwykDUtXaKnEQUiReiI52M3vhBAVmRl1DTwX+xJjdp17TkDshWioq3vsKtowSBt7eju

ztnU7xyS2g2XsRkp0L8NGtA6kIW1LZvUUD6OfN3dsFOZMRFmLXjMvWOCn+A2k87mon2z

rEMXX+zU+g4j5/7R9dl9qb+v5MkXylcgKVrXx3/akTDVbfk8BADejiM20FXGN4XDqrOA

z6azs/14qkvvZiH1vhrVhIMgbzy8si864lirE2J2YKcgWK5MXcy3zrY2t4IO0HMbONZK

tt8g==

ARC-Message-Signature: i=1; a=rsa-sha256; c=relaxed/relaxed; d=google.com; s=arc-20160816;

h=list-id:list-unsubscribe:reply-to:mime-version:date:to:subject

:message-id:from:dkim-signature;

bh=oMI0usDG210zNBNaRijk6ss9HEYFI5LreIegG7NV5VM=;

b=fF/FBqI+dHHhJwXP73exu7pVALIgXYesFYKQMn9u2tmT27K69Ok53dqwQ9a0NOeIMO

n0Eke4dfIBELZLB7FahLAL8QoFFysPjAGNduqfE//K18+86n7Wg/jMbBr4BJGL9ltloH

f5IzlIz2HOp12XCcyAy+WVsUhDDy8zuInUlyUrIF+5mnf9NPPVCaIsHI7N9MLXkgbsZX

UpS6x5GYJOhFlFe+QvR7/pfqhbP0ciKBrPN49TVSJF2EeH9/SewYuJlh5dZoZpsydD8L

AxiqPBH+3tqdnMaaOnQSZ26KBrsnCCBFAaZ8re51JwVdO8p3C/bGWOXraExrpH1WP+JY

5NFQ==

ARC-Authentication-Results: i=1; mx.google.com;

dkim=pass header.i=@i.drop.com header.s=scph0618 header.b=fZScuZfV;

spf=pass (google.com: domain of bounce-1657185485459.475823232258128637708151@i.drop.com designates 147.253.215.244 as permitted sender) smtp.mailfrom=bounce-1657185485459.475823232258128637708151@i.drop.com;

dmarc=pass (p=QUARANTINE sp=QUARANTINE dis=NONE) header.from=drop.com

Return-Path: <bounce-1657185485459.475823232258128637708151@i.drop.com>

Received: from mta-215-244.sparkpostmail.com (mta-215-244.sparkpostmail.com. [147.253.215.244])

by mx.google.com with ESMTPS id s144-20020a632c96000000b0041160e45f31si305281pgs.97.2022.07.07.07.01.04

for <someone@port.ac.uk>

(version=TLS1_2 cipher=ECDHE-ECDSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256 bits=128/128);

Thu, 07 Jul 2022 07:01:04 -0700 (PDT)

Received-SPF: pass (google.com: domain of bounce-1657185485459.475823232258128637708151@i.drop.com designates 147.253.215.244 as permitted sender) client-ip=147.253.215.244;

Authentication-Results: mx.google.com;

dkim=pass header.i=@i.drop.com header.s=scph0618 header.b=fZScuZfV;

spf=pass (google.com: domain of bounce-1657185485459.475823232258128637708151@i.drop.com designates 147.253.215.244 as permitted sender) smtp.mailfrom=bounce-1657185485459.475823232258128637708151@i.drop.com;

dmarc=pass (p=QUARANTINE sp=QUARANTINE dis=NONE) header.from=drop.com

X-MSFBL: 6Li1OAD6jdxrnkaoy/Hp4l4bxHUhsaA7/9w1iFnYAa4=|eyJjdXN0b21lcl9pZCI

6IjEiLCJyIjoibWlrZS5tZXJlZGl0aEBwb3J0LmFjLnVrIiwic3ViYWNjb3VudF9

pZCI6IjAiLCJ0ZW5hbnRfaWQiOiJtYXNzZHJvcCIsIm1lc3NhZ2VfaWQiOiI2Mjk

4ZjdhNGM2NjJlNWRjNTBlZSJ9

DKIM-Signature: v=1; a=rsa-sha256; c=relaxed/relaxed; d=i.drop.com;

s=scph0618; t=1657185527; i=@i.drop.com;

bh=oMI0usDG210zNBNaRijk6ss9HEYFI5LreIegG7NV5VM=;

h=From:Message-ID:Subject:To:Date:Content-Type:From:To:Cc:Subject;

b=fZScuZfVPkO10/ytHgvYkX2WAWsxyqr5QejjTPzYZAwCFcUlGH014uocHgPrgS05I

KxUT2cm2BPQSd1ikShdeswe8MptNWMkE4fqIna17w3+CDinB5hRJ426ojqUHORMjB7

R0jADRfBZF+GDuRCMSKBOxKTCTEgPZzj/H+ddS0M=

From: "Drop" <info@i.drop.com>

Message-ID: <05.EE.19583.7F4A6C26@gy.mta2vrest.cc.prd.sparkpost>

Subject: Drop + MiTo Serenity Desk Mat, Phangkey Amaterasu Desk Mat, Drop GMK White-on-Black Custom Keycap Set and more...

To: "Someone" <someone@port.ac.uk>

Date: Thu, 07 Jul 2022 09:18:09 +0000

Content-Type: multipart/alternative; boundary="_----cGGBgCxDlmJHT7JNSry5qA===_E0/C1-29399-27466C26"

MIME-Version: 1.0

Reply-To: support@drop.com

List-Unsubscribe: <mailto:unsubscribe@i.massdrop.com?subject=unsubscribe:ch4jzusTih96iuHiPvllEJD8RtThf9s8fddYQJW3G8Q~|eyAicmNwdF90byI6ICJtaWtlLm1lcmVkaXRoQHBvcnQuYWMudWsiLCAidGVuYW50X2lkIjogIm1hc3Nkcm9wIiwgImN1c3RvbWVyX2lkIjogIjEiLCAic3ViYWNjb3VudF9pZCI6ICIwIiwgIm1lc3NhZ2VfaWQiOiAiNjI5OGY3YTRjNjYyZTVkYzUwZWUiIH0~>

List-Id: <massdrop.1.0.sparkpostmail.com>We’ll go through some of the more interesting parts of that shortly, but the key thing to remember is that the original sender (or any “hop” along the way) can insert anything it wants into those headers, so they cannot be trusted.

Or rather there are variable levels of trust.

The Headers

From: "Drop" <info@i.drop.com>So the first thing to say is that the “From” header is likely to be the least trustworthy header in there. Whilst you probably can’t change where your emails “come from”, anyone using custom software (or crafting their own emails by hand) can put anything they like in there. So if it says “someone@port.ac.uk” there is no guarantee that it was really me that composed it (although there is some measures in place to make forging @port.ac.uk email addresses harder but not impossible).

One thing to look for are whether the two parts of the “From” header match or make some kind of sense – in this case we have “Drop” and <info@i.drop.com> which does match (in the loosest sense of the word). An example from a different email doesn’t look quite the same: “SleepConnection” <info@makeupfling.co> (taken from a real spam message).

Reply-To: support@drop.comThe next header to look at is the “Reply-To” header which may or may not be present – it effectively redirects replies to a different address. If the address included (support@drop.com) has a different domain (the bit after the “@”) then it becomes a bit more suspicious.

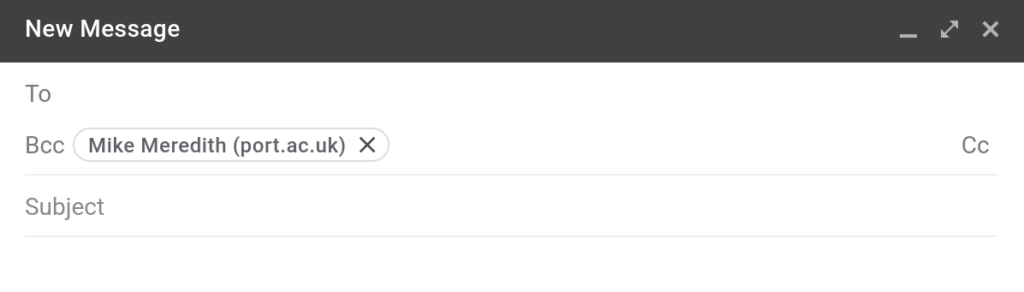

To: "Someone" <someone@port.ac.uk>And onto the “To” header (and to a certain extent the “Cc” header). This doesn’t necessarily contain your email address; nor is the absence particularly suspicious – there is in addition to the “CC” header (which also contains email addresses the email is to be delivered to), there is also an invisible “Bcc” header.

Legitimate email takes the email addresses from the “To”, “CC”, and “Bcc” headers, and adds those addresses to the “envelope” (which isn’t shown in the headers). It will also remove the “Bcc” header to preserve privacy.

Malicious emails populate the “envelope” without reference to the headers; which basically means that if the “To” field contains a name you do not recognise there is a slightly more suspicious. But if it contains your own email address that doesn’t make it trustworthy – it’s neutral.

Date: Thu, 07 Jul 2022 09:18:09 +0000Probably not the most significant header to inspect, but there is no harm checking for impossible dates – either in the future (watch out for time zones) or in the past.

DKIM-Signature: v=1; a=rsa-sha256; c=relaxed/relaxed; d=i.drop.com;

s=scph0618; t=1657185527; i=@i.drop.com;

bh=oMI0usDG210zNBNaRijk6ss9HEYFI5LreIegG7NV5VM=;

h=From:Message-ID:Subject:To:Date:Content-Type:From:To:Cc:Subject;

b=fZScuZfVPkO10/ytHgvYkX2WAWsxyqr5QejjTPzYZAwCFcUlGH014uocHgPrgS05I

KxUT2cm2BPQSd1ikShdeswe8MptNWMkE4fqIna17w3+CDinB5hRJ426ojqUHORMjB7

R0jADRfBZF+GDuRCMSKBOxKTCTEgPZzj/H+ddS0M=The significance of this header becomes relevant later on … as it is, it is a claim that the listed headers and the body of the email message have been digitally signed. Of course it has to be verified which comes later …

Received-SPF: pass (google.com: domain of bounce-1657185485459.475823232258128637708151@i.drop.com designates 147.253.215.244 as permitted sender) client-ip=147.253.215.244;This is quite similar to the DKIM signature in that it is a test of whether the email comes from a mail server that the associated mail domain designates as a legitimate source.

Authentication-Results: mx.google.com;

dkim=pass header.i=@i.drop.com header.s=scph0618 header.b=fZScuZfV;

spf=pass (google.com: domain of bounce-1657185485459.475823232258128637708151@i.drop.com designates 147.253.215.244 as permitted sender) smtp.mailfrom=bounce-1657185485459.475823232258128637708151@i.drop.com;

dmarc=pass (p=QUARANTINE sp=QUARANTINE dis=NONE) header.from=drop.comNow this claims to be a header added by Google (mx.google.com) giving the results of an authentication test – in this case we can see that the DKIM test passed – so the previous DKIM signature has been verified, the SPF test has passed, and the DMARC policy has passed – so there are good grounds for the sender of the domain is genuine.

This doesn’t mean that the email is genuine; just that the sender domain is valid.

Received: from mta-215-244.sparkpostmail.com (mta-215-244.sparkpostmail.com. [147.253.215.244])

by mx.google.com with ESMTPS id s144-20020a632c96000000b0041160e45f31si305281pgs.97.2022.07.07.07.01.04

for <someone@port.ac.uk>

(version=TLS1_2 cipher=ECDHE-ECDSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256 bits=128/128);

Thu, 07 Jul 2022 07:01:04 -0700 (PDT)

There’s quite a lot of information to be found in the “Received” headers – bearing in mind that headers can’t be totally trusted. In this example, the very first couple of lines claim that the message was received by mx.google.com (which looks legitimate) and was sent by mta-215-244.sparkpostmail.com.

The appearance of the hostname twice is because the first occurrence is what the sending mail server thinks it’s name is, and the second is Google’s (in this case) attempt at verification based on the network address. Matching is a good sign.

The Body

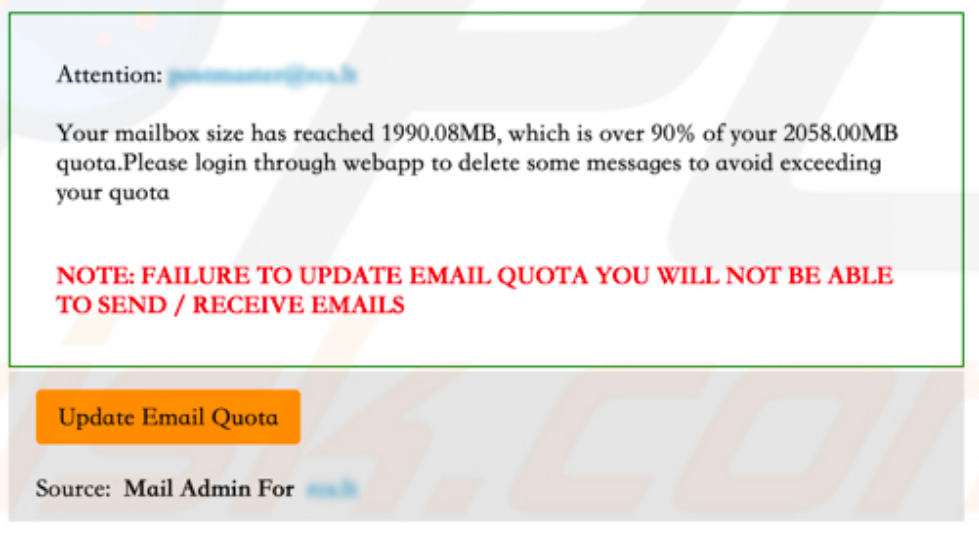

If you have read up to this point, you are probably already aware of the indications within the body of an email that make it look suspicious including but not limited to :-

- Links to sites labelled as one thing, but with the address of something else (i.e. looks like https://foo.com/ but actually goes to https://foo.com.bad.place).

- Impersonal salutations (“Dear Friend”) although personally addressed email isn’t a guarantee.

- Offers to good to be true – when was the last time you won a prize in a competition you didn’t enter?

- Strange wording. Either unnaturally good English or ridiculously bad English. Particularly from people you know or have corresponded with before.

- “Unusual” requests – especially requests to bypass standard procedures.

Final Assessment

As hinted at previously, an email may have suspicious indications but still be legitimate and an email may have no suspicious indications yet still be malicious. Determining which emails are legitimate and which are not, is not an easy thing to do – or it would be done automatically with total accuracy.

In fact a certain amount of illegitimate email is detected automatically and blocked; probably far more than we’re aware of. So we’re usually stuck determining the legitimacy of “edge cases”.

In assessing an email we look at the number of suspicious elements – if high enough we can judge it to be illegitimate. In areas of doubt, it is advised to verify the email contents “out of band” – with a phone call, checking with a colleague, or contact via an email address pulled out of a contacts database (and not the email).