Yes, this is another blog posting about password strength, which we do keep going on about. That is because :-

- The password audit still shows that people are not getting the message (although for active staff we’re doing a great deal better than we used to).

- We continue to get security incidents related to compromised account passwords although probably a majority of these incidents are probably relating to phishing attacks rather than simple password strength.

Passwords are tedious, but there is in practice very little choice other than to set long and strong passwords to protect yourself and the University. Those who have had compromised accounts can attest to the pain of having an inbox crammed with thousands of spam bounces … and that’s nothing compared to some of the hair raising stories I’m not free to talk about.

Length

Password length is the single biggest factor in determining password strength – short is weak, and long is strong. Mathematically the strength of a password can be calculated with a formula :-

(Strictly speaking that is the maximum possible information entropy given that each character is chosen perfectly randomly which would require passwords such as: wJv9eqmvGXrjUld7IKVLugAbCdpJ99KI4LDTEeJUD4c)

The most important part of that equation in terms of making a password more random (“stronger”) is the length.

This is why we are beginning to recommend a password length of 14 characters!

Passphrases

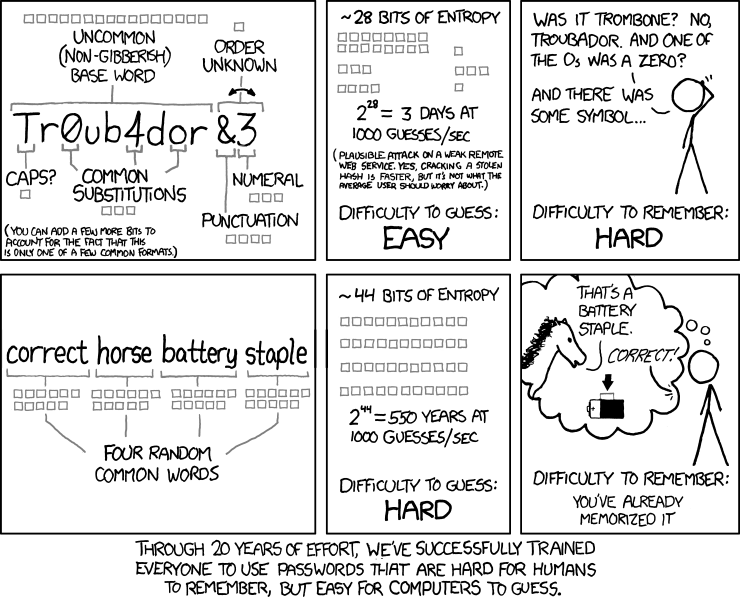

(the following is from Xkcd)

We recommend a method for generating passwords (or pass phrases) involving words :-

- Choose three to four random words. At least one of the words should be the kind of word not found in the vocabulary of the average Daily Fail reader. Such as pink, blank, whistle, prepositional.

- Capitalise at least one of the words at the end: pinK, blanK, whistlE, prepositionaL

- Pick one random symbol such as “/”, “<“, “#”, “@”, “=”, “;”, and insert in between the words: pinK/blanK/whistlE/prepositionaL

As an alternative you can use a rather useful password generator. It looks complicated, but once you load the “XKCD” preset, you are 9/10ths of the way.

Store the new password in a proper password manager (such as KeePass or KeePassXC), and then set your new password.

Safe Password Usage

- Do not tell someone what your password is. Especially your chosen password to your university account(s).

- Do not use the same password in multiple services – if one service gets compromised all your accounts with the same passwords become unsafe (or at risk).

- Where available, turn on multi-factor authentication (such as on your Google account). In the case of your university account it will not protect authentications that do not support multi-factor authentication but it will protect your university Google account. Even from phishing attacks!

“But They Aren’t Interested in Me”

Yes they are.

Attackers do want special accounts but they’re quite willing to work with ordinary accounts. We regularly see compromised accounts used by attackers to do things that are irrelevant to the account itself – specifically sending thousands of spam messages. Of course that is just what we can see!

Don’t underestimate the damage that can be caused by sending thousands of spam messages – not only do you get a very messy inbox to clean up, but your email address gets a permanent loss of credibility.

So yes you are a target, not because of who you are but of what you have (an account).

More on Multi-Factor Authentication

Multi-factor authentication (sometimes called “two step” although that makes me think of dancing which is scary enough to me never mind others) is a method by which a service (in particular anything provided by Google) can ask “can you confirm that it’s really you”. It doesn’t routinely ask this question – on my work desktop workstation, I typically get asked less than once a month.

It asks when it doesn’t recognise the machine you are connecting from (or that confirmation happened too long ago).

So whilst it does get in the way occasionally, the reduction in risk makes it well worth the trade-off.