Yes there really is such a time as 23:59:60 … at least there is on the 30th June 2015, when a leap second is inserted into standard time (I’ll gloss over exactly what that is as the full details would go on for some time). The leap second is being introduced to compensate for the fact that atomic clocks are accurate enough that the Earth’s slowing rotation means that the potential exists for standard time to deviate from planetary time.

Why does this matter? Unless you are a time geek or have a serious need for time accuracy, the only aspect of this that matters is the effect on servers and services. Historically servers have not always dealt well with the insertion of a leap second – sometimes requiring a reboot. Whilst things should have improved by now, information from certain conservative vendors indicates that problems may still occur.

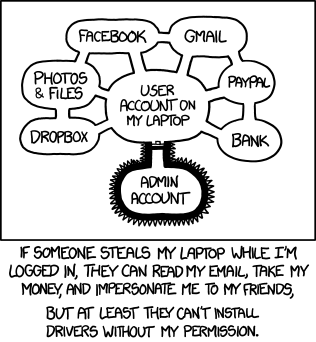

And what does this have to do with security? In a word: Availability. The “a” in CIA. No, not that CIA.

The Nitty Gritty

In detail, what happens when a computer inserts a leap second?

Various things, but the first thing that happens is that the computer inserts a leap second. The software used to do this (a very tiny piece of code) is obviously not called very often, and has itself been the cause of many of the problems that occurred when past leap seconds were inserted.

The next obvious thing that happens is that the leap second will cause the following sequence of time :-

23:59:58 23:59:59 23:59:60 00:00:00

The emphasised time is the leap second, and this time does not normally appear. Poorly written software may start acting strangely when it sees such a time.

In addition, some systems attempt to avoid this situation by repeating a second :-

23:59:58 23:59:59 23:59:59 00:00:00

This also causes poorly written software to start acting strangely. To be fair nobody expects time to go backwards, which is what appears to happen here.

In addition software could have problems with the “incorrect” number of seconds in a minute, hour, or even day. Undoubtedly there are other potential issues too.

The Work Around

The intention is that IS will avoid the leap second issue as much as possible with a work-around. A day or two before the leap second occurs, the University NTP servers will be blocked from communicating with the world’s NTP servers so they will not learn about the leap second.

And on the morning of the 1st July, the block will be reverted and the NTP servers will catch up with the rest of the world.

Because our master NTP servers never learn of the leap second, no client NTP system will learn of it either. This should prevent the leap second issue from occurring unless :-

- Something is not using NTP.

- And it has leap second support with a recent list of leap seconds.

This work-around will mean that we are running a second ahead of “real” time for some time.